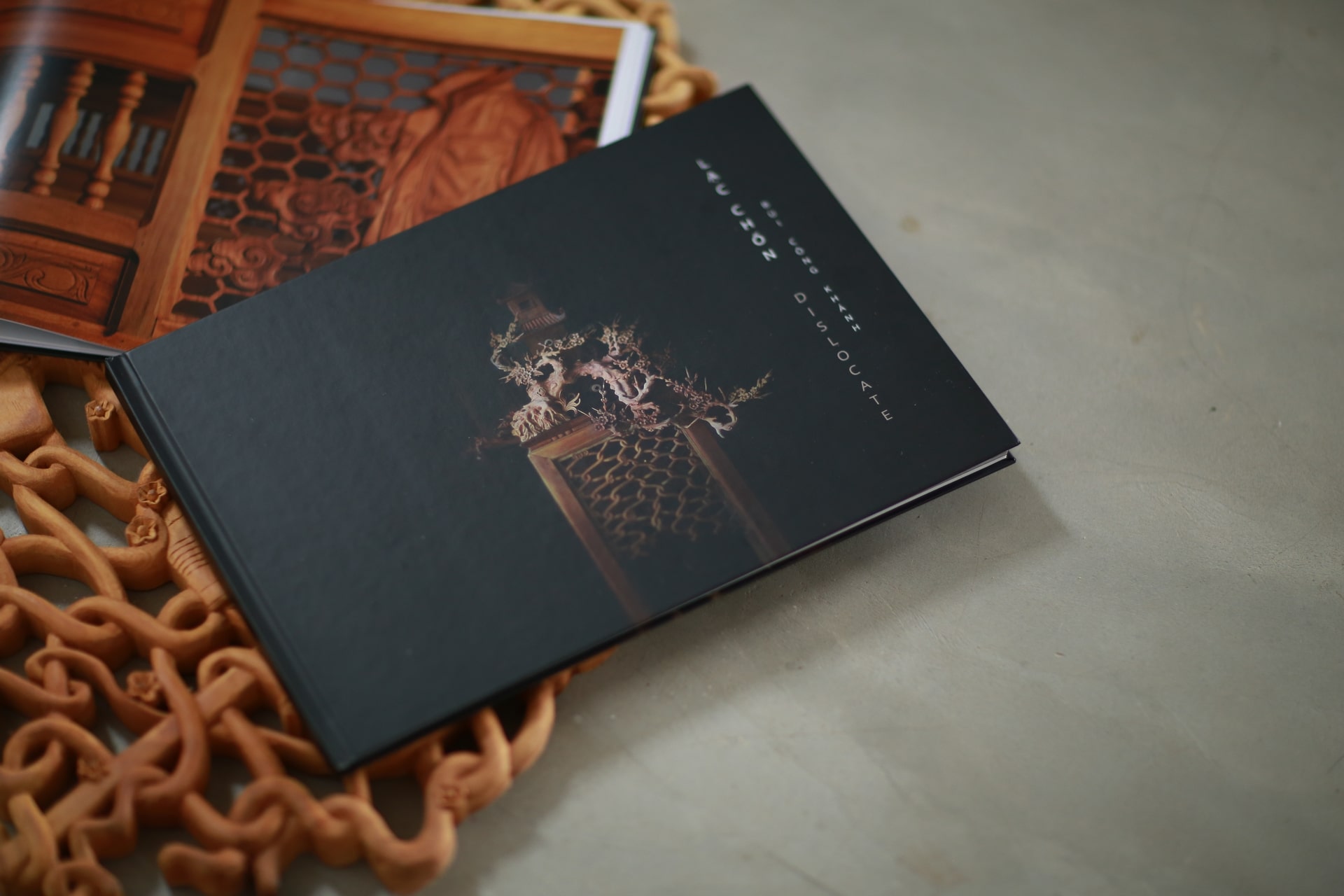

DISLOCATE

Year: 2014-2016

Material: Jackfruit wood, cotton, acrylic, bronze, stone

Multiple components, dimensions variable, unique

Curated by Zoe Butt

The M+ collections

Photographs by Nguyen Dzung, Tran Minh Thai, Bui Cong Khanh

DISLOCATE was exhibited in :

-Bui Cong Khanh’s solo show “DISLOCATE” at The Factory Contemporary Art Centre, Ho Chi Minh city, 2016.

-‘Singapore Biennale 2016: An Atlas of Mirrors’, Singapore Art Museum,2016

– artwork “ Dislocate” has been selected among the shortlisted for the 11th Benesse Prize.

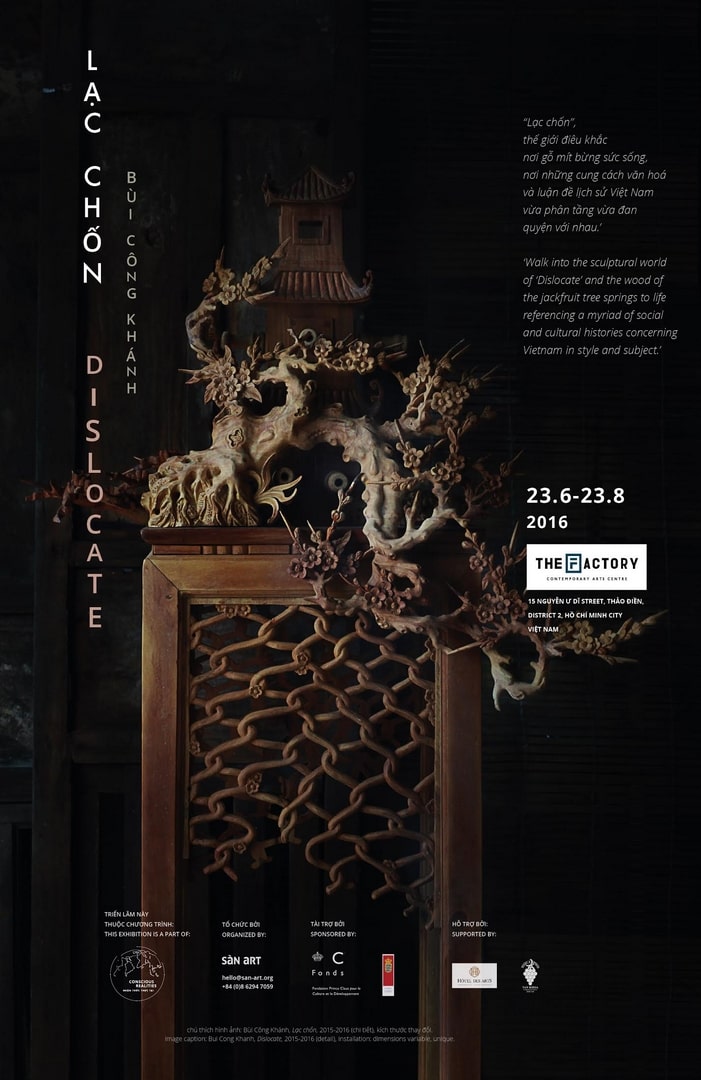

DISLOCATE – Zoe Butt

Walk into the world of ‘Dislocate’ by Bui Cong Khanh and the wood of the jackfruit tree springs to life as a stunningly carved bunker ; its architectural beams, wall panels and ‘guardians’ referencing a myriad of social and cultural histories concerning Vietnam, via style and subject. Working with a team of senior expert wood carvers and carpenters from Hoi An over a two year period, ‘Dislocate’ embraces a complex interwoven set of narratives that pivots around this ancient city on the central coast of Vietnam – a city at the heart of Bui Cong Khanh’s practice and family history.

Hoi An is a place where the brilliance of Vietnam’s eclectic past lives in vibrant array. It is an ancient site with the imprint of many differing custom and belief, beginning as the maritime jewel of the Cham Kingdom; its wooden courtyard dwellings persist with their tiled roofs in stunning recall of 17th Century Chinese and Japanese immigrants; its dining tables remain imbued with a cuisine offering a delectable fusion of local herb and foreign spice; coastline remains guarded by bunkers from the Colonial era; while its fields are still tilled with ox and cart. Bui remains fascinated by such interconnected living histories that struggle and persist in Vietnam as a consequence of an imperial and occupied past. For him, Hoi An is a unique visual testament to this confluence of history, believing that seeking to define and celebrate a belonging to this community is a process of dislocating time and space – a re-assimilation of memory, material, technique and custom – indeed he believes this is what honors his culture as thriving.

…….

‘Dislocate’ is a kind of fortress. The central structure, likened to a bunker, is deliberately left incomplete; its roof and walls are not solid, possessing space between beams where wall panels are spread randomly throughout. Taking traditional imperial architectural techniques of Hue (the ancient capital of Vietnam on its central coast) as its style, Bui chose the design of defense as its structure – it has only one entrance, its roof angled to hit the ground at the opposite end. The wood is a mixture of tones in yellow: the brighter color indicative of the youth of the jackfruit tree, in comparison to a darkened complexion illustrative of age. In ‘Dislocate’, Bui combines the antique with the newly carved. He has literally taken apart the bones of a traditional home and re-purposed particular structural and decorative elements within his own design. The compass of this fortress is guarded outside by what could be likened as sentinels: four- miniature Buddhist pagoda sitting atop their own tall square plinth, each dramatically near-suffocated by penjing in representation of the seasons that govern the cycle of time – Spring, Summer, Fall and Winter. This is a quietly theatrical installation, a structure poised ready to protect from eminent danger – but from whence does this danger come? For Bui, this fortress has been deliberately dislocated from any single identified threat, standing as monument to the historical resilience of Vietnam, a country that has successfully ousted the territorial expansionism of the Chinese, French, Japanese and American trade and military interests. Peer closely inside this fortress and you will note that certain wall panels are lovingly embossed with various flora, fauna and objects that directly refer to these historical moments of great conflict – an American GI helmet; lotus flowers, a Vietnamese military jacket, a phoenix, an axe, even a grenade (amongst many others). To understand the medley of these metaphorical symbols and structures it is useful to delve briefly into the history of Hoi An and its strategic coastal location.

Hoi An is anchored in the downstream of Thu Bon river on the central coast of Vietnam in Quang Nam Province. The site of Hoi An came to prominence in the 2nd Century as the commercial capital of the Cham Empire, possessing the largest port in South East Asia at that time. By the late 1500s, following great territorial disputes between the Cham Kingdom and the Dai Viet, Hoi An was established as a major Vietnamese trading center in the South China Sea. The town of Hoi An soon possessed a Japanese quarter (the Japanese bridge, ‘Chùa cầu’, being a popular tourist attraction today), and with the collapse of the Chinese Ming Dynasty in 1644, Hoi An also embraced many Chinese refugee – predominantly from Fujian, Guangdong, Chaozhou, and Hainan – who built pagodas, schools, and medical clinics amongst many other civic facilities and services. Until

the end of the 18th Century, Hoi An earned significant reputation in the eyes of European, Chinese and Japanese merchants as a critical center of commerce in the Asian region selling goods such as pepper, rhino horn, gold, silk and sugar (amongst a plethora of other rare and deemed exotic goods). Shipwreck discoveries also give testament to the ceramic industry at this time, providing evidence that the porcelain of Hoi An was heavily prized in Europe, and as far as Sinai, Egypt. Hoi An’s international reputation as a commercial hub began to wane by the late 1800s due to imperial edicts by Emperor Ming Mang who sought to limit all foreign trade to a single sea port – that of Da Nang. This city would go on to be the key strategic trading and military outpost of the French in their eventual formalization of French IndoChina (1887), and later the American forces during the Vietnam War. The political rise and growth of Da Nang as a trading harbor thus quickly overshadowed Hoi An, which soon became somewhat of a sleepy tourist township. However to the locals of Da Nang, such as the immediate family of Bui Cong Khanh, Hoi An was an ancestral site, a cultural historical center that triggers the memory of Vietnam.

Bui Cong Khanh was born in Da Nang in 1972, in what was then the third largest city in Vietnam. It was a turbulent time with the country caught in the throes of a civil war (locally referred as the ‘American War’) that had become a global outcry as the world’s super-powers interfered in fear of Vietnamese Communist success. Da Nang was a coveted air base for the American GI at that time and Bui’s father was a military officer with the Republic of South Vietnam. After 1975, Bui recalls miserable conditions, hunger crept from urban to rural areas, there was a great rationing of resource across the country and rice was hard to find. Bui remembers his mother’s thrift in cooking the daily meals and, like her fellow neighbors, inventing all manner of ways to cook the one plant that was somewhat readily available – jackfruit.

‘Dislocate’ is deliberately carved entirely from the wood of this mít tree – a material he long marveled for the multifarious ways this plant had been made of use by his family. His father was a carpenter whose skill in carving this malleable timber was intriguing to a young Khanh, while his mother was adept at turning its bright yellow fruit into all manner of delectable dishes – jackfruit salad, jackfruit and coconut dessert, jackfruit soup – for this was a tropical plant cherished as a Vietnamese delicacy (raw, unripe and cooked). It is a plant easy to grow in wet mountainous climate, resilient in drought conditions, and as a perennial crop has long been cherished during times of scarcity.

‘In those dishes that my mother made from jackfruit – the young jackfruit cooked or used to make soup, jackfruit testicles (male flower jackfruit) with shrimp, jackfruit eaten as dessert … I still remember those things today … what my mother did makes me think of the reign of King Minh Mang, when the citizens were starving, jackfruit helped the people overcome distress’

“In 1831 according to the old ‘Records of National History’ [“Quốc sử di biên”], King Minh Mang’s ordinance once stated: “Decree to all towns, villages and residents to grow jackfuits, one tree every 5 meters; all river’s dikes, from large to small, to grow willow trees, and all abandoned gardens to grow jute hemps”.

During the 17th year of Minh Mang’s rule (1837), he commanded the image of the jackfruit be embossed on one of nine dynastic bronze urn in Hue‘s loyal court, signaling this fruit as a cultural national treasure of pride and bounty. Indeed it is common to this day, to find the shade of a jackfruit tree in the front garden of a Vietnamese rural home, especially in the central belt of Vietnam where the climate is favorable. However for Bui, the choice of jackfruit for this installation is also an attempt to highlight the current trade in the plant. Jackfruit is of high demand across South

East Asia (the plant is native to much of this region) and its resilient wood highly sought after by domestic tastes desiring antique style housing and furniture (a result of a fast modernized Vietnamese middle class, tired of concrete, metal and plastic that was prevalent over the past 40 years). Due to alarming deforestation across Vietnam, farmers of the jackfruit plant increasingly refuse the logging of this tree as its fruit is often in farmer’s critical livelihood. Where once fishing boats would dot the coastline, produced from the wood of the mit, Vietnam now has metal military beasts patrolling (especially along the South China Sea). It is ironic that the luxury tastes of a developing Vietnam should eschew the metal and concrete in their homes, yet they allow such materials to dominate their country’s industrial growth and pollute its habitat. If we look more closely at this paradox of identity and consumption, we will see that such irony is a much broader cultural complexity in Vietnam.

Bui recalls a visit with his father to his family shrine in Hoi An when he was 20 years old. This family shrine possessed several framed photographs of his ancestors that always sat in this specially designed interior wall recess, amongst offerings of pomelo, incense and tea. On this day however, Bui noticed something he had not registered before – at the very top of this family shrine was a shelf with a little curtain in front of it. Climbing up to a higher platform to reach this part of the shrine, Bui discovered a hand painted image on paper of ‘Quan Cong’ – a great historical Chinese deity. Bui remembers the shock in his voice when he asked ‘Father, are we Chinese?’; his father, quite casually, confirmed. Pointing at their photographs, he replied ‘Your great great grandmother was from Hue (Vietnam). Your great great grandfather was from Fujian (China)’. To the shocked young Bui, these hidden faces were of great fascination, but sadly he did understand that the secrecy of their presence was a result of Vietnam’s historically suspicious relationship with China. Despite the fact that Vietnam has innovated so many inherited traditional practices from China, the aggression of its northern neighbor remains greatly feared in their determination to challenge Vietnam’s sovereignty. Thus Bui understood that this curtained shrine was not his family rejecting who they are, but an acceptance they must respect their ancestors quietly, in order to survive an increasing social stigma against the Chinese.

It is this quiet tolerance that Bui interweaves in ‘Dislocate’. This is a fortress whose walls are held together by memories of great warring pasts, the irony of its beauty encapsulated in its wooden ‘penjing’ which threaten to engulf these four guardians of worship. In ‘Dislocate’ it is as if this ancient art – to nip, tuck, graft and nudge a plant’s growth into a particular shape – has gained its own powers, for here it is the penjing that seems to prevail over man’s institutions of spiritual aspiration.

‘Dislocate’ is Bui Cong Khanh expressing his appreciation for not only his ancestry, but also his paying homage to Vietnam’s historical resilience. It is an artwork that highlights instruments of social control; sharing the dilemma of living a discriminated ethnicity; while also questioning who has the right to control what is natural, man-made or celestial. Bui Cong Khanh asks – is it possible for history to be revisited without bias? In the absence of any specific threat within this installation, Bui gives us space to pause, to contemplate what social bias we may carry unknowingly, to ‘dislocate’ ourselves from our perceived reality in a hope to re-conjure its largesse.